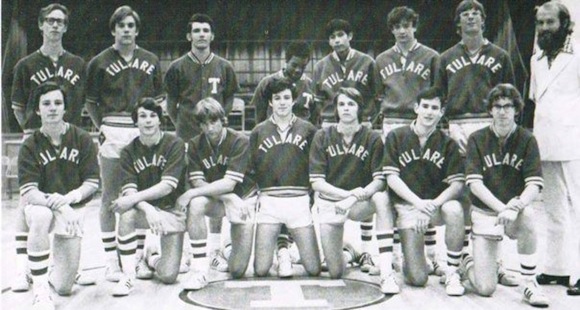

That’s me, kneeling in front on the right, next to Coach Gentry.

I played–actually played–on my high school basketball team in ninth and tenth grades. That was in Arizona. Then we moved to California, where I attended Tulare Union, a school twice as large. I made the junior varsity team, but that’s as far as it went. Belonging to the team and seeing action are two different things.

In our daily practices, I worked and sweated and grunted just as hard as my first-string teammates. On game days, I suited up in a uniform identical to everyone else’s, except for the number and the lack of sweat-stains. I participated in the pre-game warm-up drills–free throws, fast breaks, lay-ups, etc. Just before tip-off, I added my hand to the huddle and joined in a zealous “Let’s go!”

But after that, it was, “We’ll take it from here, Steve.” If you don’t have it, you don’t have it. I didn’t have it, and didn’t know where to find it.

So I would plop into my seat at the end of the bench, cheer my teammates to victory, dream of a never-meant-to-be-game-winning-honor-and-glory-forevermore-last-second-jumpshot, and wonder what in the world I would do if the coach actually put me in the game.

“What? You want me to go out there, onto the court? But I might accidentally touch the ball and make us lose the game. Are you sure, Coach?”

Coach Gentry was an easy-going guy in his first year as a basketball coach. To defend myself, I could claim he was too inexperienced to recognize talent when he saw it. The truth is, even a rookie coach can recognize a lack of talent. And so I collected splinters, watched, rooted, hollered, and brought home a clean uniform for Mom to wash.

Cut to Creative Writing class. There, I starred for Mrs. Harbour. I sunk half-court swishers, slugged home-runs, threw touchdown bombs, drilled aces. I think she liked me.

That semester, Mrs. Harbour assigned a writing “decathlon,” you might call it, in which we had to compose various types of writing. A rhymed poem. Free verse. Haiku (the most ridiculous thing this side of Form 10-40, don’t you agree?). An essay. A short story. An interview. A news feature. And a parody.

Ah, the parody. Only a week or so remained of the basketball season, and I didn’t plan to try out for the team my senior year. Nothing to lose. So here’s what I wrote for Mrs. Harbour.

Mr. Gentry is my basketball coach; I shall not play.

He maketh me to lie down at night with aching muscles;

He wind-sprinteth me beside cool-drinking fountains.

He restoreth my thirst.

He keepeth me off the playing floor, for his team’s sake.

Yea, though we lead by 50 points, I will fear not messing up, for I still won’t play.

In practice, thy whistle and thy slave-driving, they tireth me.

Thou anointest my body with sweat;

My pores runneth over.

Surely exhaustion, anonymity, and depression shall follow me all the days of the basketball season.

And I shall dwell at the end of the bench forever.

It was just for Creative Writing class. Mr. Gentry would never see it…would he?

A couple days later, Coach Gentry stopped me between classes.

“Mrs. Harbour showed me your poem,” he said, as all color drained from my face and I envisioned running about 5000 laps. “It was funny.”

“Uh, thanks,” I said, quickly scooting away to my locker.

Had I known Coach Gentry would read that parody, would I have written it? I doubt it.

But it gets worse. Mrs. Harbour immortalized that parody at Tulare Union High School. For years afterward, she distributed mimeographed copies to her English classes as an example of a good parody. A real live literary masterpiece by someone who attended TU. A treasure from her star pupil, who at this very moment was no doubt writing The Great American Haiku. (“Can anything good come out of…yes! And I taught him everything!”)

For all I know, that frivolous parody still makes the rounds at Tulare Union. It is my only mark on that school, my legacy. If Mr. Gentry remembers me, it’s not because of my forgettable jump shot. It’s because of that one silly little poem.