I’ve been reading quite a few books about the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Most have been very good, and they’ve all been quite different.

I’ve been reading quite a few books about the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Most have been very good, and they’ve all been quite different.

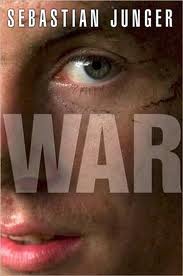

“War,” by Sebastian Junger, is my favorite. Junger is best-known for his 1997 book “The Perfect Storm,” a phenomenal work which became an international bestseller. But he has proven himself as a war reporter in such places as Bosnia, Liberia, Cyprus, Kashmir, and now Afghanistan.

Junger is an amazing writer. When I saw that he had written a book on Afghanistan, I knew I had to read it. Likewise for Jon Krakauer, another master wordsmith, who wrote “Where Men Win Glory” (which I reviewed previously). I was blown away by the poetry of “The Perfect Storm.” While the writing of “War” is much different, it’s still brilliant.

For over a year, Junger and a photojournalist embedded with the 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team in the remote Korengal Valley of Eastern Afghanistan, right along the Pakistani border (a bit north of Tora Bora and the famed Kyber Pass). They especially focused on Restrepo, a small outpost, which found itself in firefights on a regular basis.

The amount of combat experienced at Restrepo and the surrounding outposts is astounding, a real eye-opener. For a while, the firefights occur practically every day. American soldiers die and are wounded frequently. Junger notes, “Most Korengalis have never left their village, and have almost no understanding of the world beyond the mouth of the valley. That makes it a perfect place in which to base an insurgency dedicated to fighting outsiders.”

The title, “War,” is interesting, as if it’s a book about war in general, rather than about a specific combat team in a specific place. But Junger does use Restrepo to generalize about warfare. He uses the experiences of soldiers in the Korengal Valley to draw analogies with previous wars and to cite various studies. We get

to know the American soldiers very well, and we get engrossed in the

life they lead in the Korengal. But through them, we learn what

soldiers in all wars, especially modern wars, experience.

In one fascinating section, he explains what happens physiologically to men during combat–pupils dilating, pulse and blood pressure approaching heart-attack levels, blood flooding the heart, brain, and major muscle groups. A high heart-rate makes it difficult to aim a rifle. At 170 beats per minute, tunnel vision and loss of depth perception occur. It’s fascinating stuff.

The best way to tell you about this book is to use Sebastian Junger’s words.

“To a combat vet, the civilian world can seem frivolous and dull, with very little at stake and all the wrong people in power.”

“War is a lot of things, and it’s useless to pretend that exciting isn’t one of them. It’s insanely exciting….Soldiers discuss that fact with each other and eventually with their chaplains and their shrinks and maybe even their spouses, but the public will never hear about it. It’s just not something that many people want acknowledged. War is supposed to feel bad because undeniably bad things happen in it, but for a nineteen-year-old at the working end of a .50 cal during a firefight that everyone comes out of okay, war is life multiplied by some number that no one has ever heard of. In some ways 20 minutes of combat is more life than you could scrape together in a lifetime of doing something else.”

“Pretty much everyone who died in this valley died when they least expected it, usually shot in the head or throat, so it could make the men weird about the most mundane tasks….The men just never knew, which meant that anything they did was potentially the last thing they’d ever do.”

One soldier told him, “There are guys in the platoon who straight up hate each other. But they would also die for each other.”

One soldier told him, “There are guys in the platoon who straight up hate each other. But they would also die for each other.”

Junger (right) says he never heard the soldiers question the validity of the war. That was a luxury for persons at the main bases, behind the lines.

He talks about “the insane amount of firepower” available to the Americans, like the big shoulder-fired Javelin rocket “that can be steered into the window of a speeding car half a mile away. Each Javelin round costs $80,000, and the idea that it’s fired by a guy who doesn’t make that in a year at a guy who doesn’t make that in a lifetime is somehow so outrageous it almost makes the war seem winnable.”

“Combat was a game that the United States had asked Second Platoon to become very good at, and once they had, the United States had put them on a hilltop without women, hot food, running water, communication with the outside world, or any kind of entertainment for over a year. Not that the men were complaining, but that sort of thing has consequences. Society can give its young men almost any job and they’ll figure out how to do it. They’ll suffer for it and die for it and watch their friends die for it, but in the end, it WILL get done. That only means that society should be careful about what it asks for.”

“Heroism is hard to study in soldiers because they invariably claim that they acted like any good soldier would have. Among other things, heroism is a negation of the self–you’re prepared to lose your own life for the sake of others–so in that sense, talking about how brave you were may be psychologically contradictory. (Try telling a mother she was brave to run into traffic to save her kid.) Civilians understand soldiers to have a kind of baseline duty, and that everything above that is considered ‘bravery.’ Soldiers see it the other way around: either you’re doing your duty or you’re a coward.”

He talks about how soldiers hold each other accountable, because sloppiness doesn’t just endanger them, it endangers everybody. “Once I watched a private accost another private whose bootlaces were trailing on the ground. Not that he cared what it looked like, but if something happened suddenly–and out there, everything happened suddenly–the guy with the loose laces couldn’t be counted on to keep his feet at a crucial moment. It was the OTHER man’s life he was risking, not just his own.”

“Humans may be the only animal that practices what could be thought of as ‘suicidal defense’: an individual male will rush to the defense of another male despite the fact that both are likely to die.”

“When men say they miss combat, it’s not that they actually miss getting shot at–you’d have to be deranged–but that they miss being in a world where everything is important and nothing is taken for granted They miss being in a world where human relations are entirely governed by whether you can trust the other person with your life.”

If you’re going to read a book about the Afghan-Iraq wars, there are several I recommend highly. But this one tops my list.