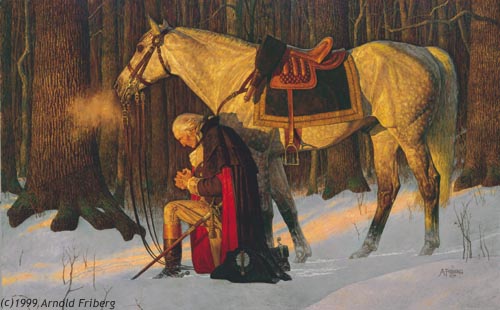

George Washington, in 1775, complained to his British counterpart about the poor treatment of American POWs. He threatened to treat British soldiers the same way, but admitted he couldn’t. Instead, though the Colonials were on the run and fighting a desperate war against a world-class army, Washington insisted that British captives be treated humanely.

In the Revolutionary War, George Washington took the high ground. Our Declaration of Independence, which he signed, said that ALL people–not just US citizens (who really didn’t even exist yet)–were endowed with inalienable rights. Whether American, British, Hessian, or whatever, every human being deserved to be treated humanely.

He wrote to his troops in September 1775, “Should any American soldier be so base and infamous as to injure any [prisoner]. . . I do most earnestly enjoin you to bring him to such severe and exemplary punishment as the enormity of the crime may require. Should it extend to death itself, it will not be disproportional to its guilt at such a time and in such a cause… for by such conduct they bring shame, disgrace and ruin to themselves and their country.”

Mistreating prisoners was, to Washington, a war crime. And he was okay with executing American soldiers who violated this standard, because in mistreating prisoners, you shame and disgrace your country.

Meanwhile, British troops severely mistreated American prisoners. That’s how they dealt with British subjects who rebelled against the King. They didn’t tolerate that from the Scotts, and wouldn’t tolerate it from Americans. The British took 31 prisoners at Bunker Hill, and all 31 died in captivity. Of 1600 Colonial POWs taken at Fort Washington, all but 800 died by 1778.

But despite the cruelty shown to American POWs, Washington insisted, “We’re going to set a different standard consistent with the values of our revolution.” While the American public cried out for revenge, for “an eye for an eye,” George Washington determined to redefine the rules of war to reflect the humanitarian principles set forth in the Declaration of Independence.

That required respecting the dignity of every human being, regardless of which side they fought on. We were not just creating something new in terms of a democracy. We were creating new ideals.

After capturing many Hessian soldiers after the Battle of Trenton in 1776, Washington declared, “Treat them with humanity, and let them have no reason to complain of our copying the brutal example of the British Army.”

He would treat British POWs as well as he treated his own soldiers–food, shelter, medical care. In that way, he would shame the British and demonstrate the moral superiority of the American cause. Plus, it might win over the enemy. After the war, nearly all of the surviving prisoners from Trenton settled in America and attained citizenship.

Washington had another motive, too, one based on his service during the French & Indian War. He observed that soldiers who mistreated prisoners were bad and unruly soldiers, and they undermined the morale of the entire army.

Washington’s example was US Army doctrine for 227 years–right up until November 13, 2001. New rules had been drawn up through Dick Cheney’s office. Cheney submitted them to George Bush during a private lunch meeting, assuring the president that they had covered all the bases legally and otherwise. And Bush, ever trustful of his VP (at least back then), signed it.

George Bush’s signature freed us from George Washington’s ideals, and ended 230 years of US military tradition. And we began torturing prisoners. From that point on, by executive order, we were no longer bound by the Geneva Conventions, no longer required to view POWs as having the inalienable rights which the Declaration of Independence said belonged to all persons (not just Americans).

So we chained prisoners, naked, in damp cells for months on end. We stood them up, naked, hands shackled overhead, for weeks at a time. We slammed their heads into walls. We humiliated them in pathetic ways. We violated every inalienable right for which George Washington fought. And that is why we can’t just let this go.